In terms of constitutional functionality and importance to the tenets of representative governance in Nigeria, we can argue that no political appointment carries more significance in the central government than the Attorney-General of the Federation. Perhaps, the significance becomes even more consequential when the position of Minister of Justice is added to the portfolio of the chief law officer.

To underscore the importance of the office of the Attorney-General of the Federation, it is one of the very rare appointments captured, both in form and function, in the 1999 Constitution.

Section 150 of the constitution clearly states that 1) There shall be an Attorney-General of the Federation who shall be the Chief Law Officer of the Federation and a Minister of the Government of the Federation, and 2) A person shall not be qualified to hold or perform the functions of the office of the Attorney-General of the Federation unless he is qualified to practise as a legal practitioner in Nigeria and has been so qualified for not less than ten years.

Section 174 of the same constitution highlights the functions of the chief law officer when it states that, “The Attorney-General of the Federation shall have power – (a) to institute and undertake criminal proceedings against any person before any court of law in Nigeria, other than a court-martial, in respect of any offence created by or under any Act of the National Assembly; (b) to take over and continue any such criminal proceedings that may have been instituted by any other authority or person; and (c) to discontinue at any stage before judgement is delivered any such criminal proceedings instituted or undertaken by him or any other authority or person.

Subsection 2 of the provision says, “The powers conferred upon the Attorney-General of the Federation under subsection (1) of this section may be exercised by him in person or through officers of his department. And, most importantly, Subsection 3 warned sternly that, “In exercising his powers under this section, the Attorney-General of the Federation shall have regard to the public interest, the interest of justice and the need to prevent abuse of legal process.”

For the avoidance of doubt, that note of caution is the most crucial provision of the Nigerian constitution when it comes to the establishment and role of the office of the attorney-general. It was not conceived or inscribed in the nation’s supreme book just to fill space. Rather, it reminds the occupier of that particular position that, while he or she has vast powers when it comes to public prosecution, protecting public interest, upholding the rule of law and preventing abuse of legal process should strictly guide the discharge of their duties.

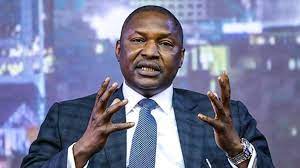

Unfortunately, of all the provisions that pertain to that highly sensitive position, there are concrete indications that Nigeria’s immediate-past Attorney-General of the Federation and Minister of Justice, Abubakar Malami, chose to disregard that sacred provision.

Recently, at a training of police prosecutors on criminal justice law in Abuja, Malami said the effective implementation of the Criminal Justice Act (ACJA) 2015 remained one of the priorities of the federal government in the area of justice delivery. However, for close to eight years, the same dispensation of justice suffered untold setbacks due to his penchant for activities which not only undermined the integrity of his office but also distracted from the discharge of his statutory functions.

Amidst a criminal justice system that stakeholders acknowledge has collapsed and is in dare need of inspired and critical intervention, it is interesting, if not appalling, to observe that Malami’s tenure was marked by allegations and scandals rather than a rigorous pursuit of reforms that would have revived or, at least, set a template to resuscitate the nation’s malfunction criminal justice system.

In October 2022, former Minister of Interior and Malami’s colleague in the Federal Executive Council, Rauf Aregbesola, said 51,541 out of the 75,635 inmates (68 per cent) in various prisons in the country are awaiting trial. He said the situation was putting undue pressure on custodial centres in the country and that the situation was the greatest challenge the service had.

“No fewer than 70 per cent of Nigerian inmates are serving time without being sentenced as they are awaiting trials. Assuming the period of waiting for trial is even small, probably it will not be an issue, we can manage it. How can you put people on trial for fifteen, or ten years, how? And they are not a small number. Some are even there forever, there is no file, there is no prosecution process, they are just there,” he said.

Simultaneously, Nigeria had a chief law officer whose ambition to be governor of his state took preeminence over the huge challenges his office was created to solve.

A case in point was when President Muhammadu Buhari signed the Electoral Act 2022 in February but urged lawmakers to expunge section 84(12) of the Act. The Section provides that, “No political appointee at any level shall be a voting delegate or be voted for at the convention or congress of any political party for the purpose of the nomination of candidates for any election.”

After the National Assembly rejected the request by President Buhari to delete the section, Nduka Edede, a member of Action Alliance (AA) filed a suit challenging the constitutionality of the provision of the section. Curiously, the suit had Malami as the only defendant. The judge agreed with the plaintiff that the provision conflicted with Nigerian citizens’ rights guaranteed by the constitution. Facts emerged that Malami gave the president the legal advice to ask the National Assembly to expunge the section from the act, as he vowed to execute it expeditiously by deleting the section from the act.

Apparently, the then nation’s chief law officer was protecting his ambition to become governor while not necessarily complying with the directive issued by Buhari to political appointees seeking to participate in the 2023 elections to resign.

By the time Malami withdrew his political ambition, he had set the justice system further aback and dented the integrity and sanctity of the office he was holding. And, less spoken about, was the amount he spent on the vanity fair and how exactly he raised such money.

It is therefore incumbent on the new administration of President Bola Tinubu to pay particular attention to the character and track record of the next AGF. Knowing that there is an enormous work left undone in the area of criminal justice reform which has implications for national security, only a professional with pedigree should be assigned the AGF portfolio.